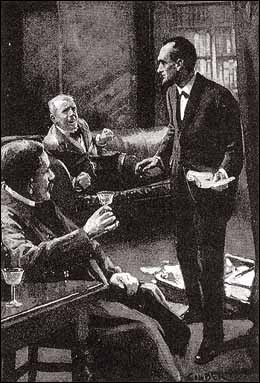

“Ah, you rogue!” cried Jones, highly delighted. “You would have made an actor and a rare one. You had the proper workhouse cough, and those weak legs of yours are worth ten pound a week. I thought I knew the glint of your eye, though. You didn’t get away from us so easily, you see” (The Sign of Four).

I have a confession to make. You see, I was once completely taken in by one of Sherlock Holmes’s disguises. There, I said it. I don’t feel any less embarrassed for having admitted it, but still, it’s the truth. It was my first viewing of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939), starring Basil Rathbone, and oh, how I laughed when that silly vaudeville singer came out, in his ridiculous striped jacket. And oh, how I chuckled to myself, thinking how Sherlock Holmes would never do anything as undignified as sing, “I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside,” while dancing merrily. And oh, how stupid I felt when that music hall performer revealed himself as the Great Detective. I had read the stories after all, how did I not I see this coming? It felt a bit like being caught off-guard at Holmes making a complex deduction or lighting his pipe; at times, the disguises seem as much a part of his character as anything else.

|

| www.basilrathbone.net |

· The Old Priest from “A Scandal in Bohemia”

A unique disguise for Holmes if only in that it failed. He appears in costume twice in SCAN, first as “a drunken-looking groom,” before becoming the “simple-minded Nonconformist clergyman.” Granted it was the entire package of circumstances (the rowdy crowd, the fire scare, the smoke bomb, and the old priest) that allowed Irene Adler to realize that she had been duped. But Holmes’s disguise didn’t serve to protect him. He is wearing it at that famous canonical moment, when bent over to unlock the door to Baker Street, Adler saunters past (in her much more effective costume) and says, “Good-night, Mister Sherlock Holmes.” Holmes is caught off-guard and very unsettled. The Great Detective has been defeated, and he doesn’t even fully realize it until the next day, when he returns to Briony Lodge with Watson and the King of Bohemia to attempt to retrieve the prize.

Holmes has a laundry list of skills at his disposal, without even considering his ability to camouflage himself: analytical and deductive reasoning, physical dexterity, safe cracking and lock picking, the ability to identify 140 different types of tobacco ash (BOSC) and 42 different bicycle tire treads (PRIO). But Holmes’s ability to disguise himself is a bit like putting on armor; it’s a skill, to be sure, but it also acts as an extra layer of protection. Holmes appears as other people when it would be unwise to appear as himself, or when he would learn more masquerading as someone else. The costumes shelter him from physical threat, and protect him from the possibility of failure.

Irene Adler saw through his disguise, and she knew who he was. She knew that she had become “an object of interest to the celebrated Mr. Sherlock Holmes.” Sherlock Holmes wasn’t just wrong in the case of “A Scandal in Bohemia”; and he wasn’t just proven wrong by a woman. He was proven vulnerable.

· The Old Bookseller from “The Empty House”

A unique costume for the reasons that Holmes employed it. Ransom Riggs says, in The Sherlock Holmes Handbook: The Mysteries and Methods of the World’s Greatest Detective, “Few things are more shocking than watching one person become another” (143). Nowhere in the canon is this more accurate than in “The Empty House.” One moment, Watson is talking to an old bookseller who is eagerly trying to sell him copies of British Birds, Catullus, and The Holy War; he turns to examine his bookcase and when he looks back, Sherlock Holmes is smiling at him—a man who by all accounts has been dead for three years. It’s hard to blame the Doctor for careening into a flat faint.

Holmes gets quite a bit of grief for being needlessly cruel to his old friend in this instance, and even he terms his use of the disguise as “unnecessarily dramatic,” but there are few factors to consider before passing judgment. While the rest of the world thinks Sherlock Holmes is dead—and that meant he could have walked down a Kensington street and not attracted any notice from random passersby—there certainly were people that were looking for the face of a dead man in the crowd. Holmes knew that one of Professor Moriarty’s confederates, Colonel Moran, had escaped capture; and most importantly, Holmes knew that he was being watched. In short, he is in danger, but most especially, he is a danger to others. If he had simply strolled casually into Watson’s practice dressed as no one but himself, the apple-seller across the street may have thought little of it, but more likely, one of Moran’s associates would have attempted to cut down Holmes before he ever crossed the threshold. And if not, Watson would have been in danger just by being in Holmes’s presence.

So in this instance, Holmes disguises himself, not just to glean information, not just for his own protection, but for the protection of others.

· “Altamont,” Irish-American Spy, from “His Last Bow”

A unique masquerade if only in terms of sheer longevity. In this story, which is chronologically the last of their adventures (taking place in 1914), Holmes tells Watson how he came to be a spy, under the behest of the prime minister himself: “It has cost me two years, Watson, but they have not been devoid of excitement. When I say that I started my pilgrimage at Chicago, graduated in an Irish secret society at Buffalo, gave serious trouble to the constabulary at Skibbareen…” Michael Walsh’s short story, “The Song at Twilight,” available in the collection, Sherlock Holmes in America, provides an interesting timeline of specifics regarding Holmes’s American excursion, including the details of his induction into the Irish secret society he spoke of, how “James McKenna” became “Altamont,” and how the ghost of a past adventure influenced that change.

Altamont is also peculiar in that he is not one of Holmes’s more complicated disguises in terms of make-up and costuming. He grows a goatee, and adopts an Irish-American accent and appropriate slang. Both of which he apparently despises and plans to do away with as soon as possible, but a disguise for Sherlock Holmes was more than just grease-paint and fake hair. As Watson tells us, “It was not merely that Holmes changed his costume. His expression, his manner, his very soul seemed to vary with every fresh part that he assumed” (SCAN). Considering this, assuming a persona for two entire years, becomes a very interesting thing indeed for Sherlock Holmes.

In “The Song at Twilight,” Holmes outlines the assumption of his new personality: “Still, no role I had played, neither stable boy, nor wizen bookseller, nor even Sigerson—when the world, including Watson, thought me dead after Professor Moriarty’s unfortunate accident at the Reichenbach Falls—could rival my new persona…With every passing day, he was becoming more and more real to me, and there were days when I hardly thought of Mr. Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street” (336). “Altamont” is interesting, therefore, in that he could perhaps be termed a person and not a persona; and serves to further accentuate the very dangerous games Holmes sometimes played with others, but also with himself.

~~~

Like Inspector Jones tells him in The Sign of Four, Holmes “would have made an actor and a rare one,” and the Detective’s ability to masquerade as almost anyone provides some of the canon’s more lighthearted moments. But as with almost everything he does, there are layers of purpose here. He uses disguise for a myriad number of reasons—to get information, to protect himself, to protect others, and perhaps even for reasons that are beyond his own understanding. Whatever the case, Holmes was a master at it, and even Watson never seemed to develop the ability to see through his friend’s subterfuges, no matter how many years they knew each other. Perhaps then I’ll stop being embarrassed about my oversight in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Probably not.

oOo

A new blog contest launches this Monday, April 25! Brush up on your Sherlock Holmes trivia, and check back here for details on how to enter and win.

yeah, I think so. I also like the Sherlock Holmes costume.

ReplyDelete