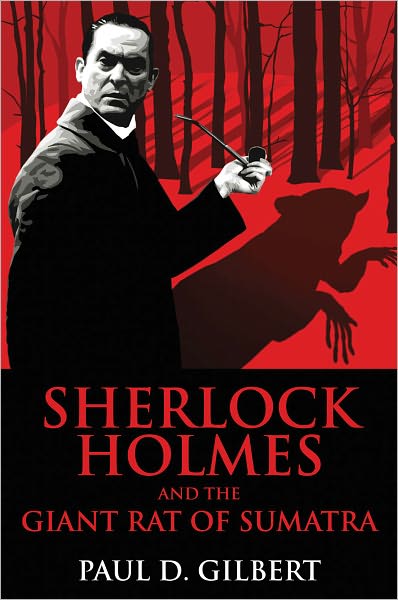

Paul D. Gilbert; Publisher: Robert Hale (April 1, 2011)

“That is as maybe, but as Watson will certainly attest, I have long insisted that most men have only the ability to see, without making a worthwhile observation. It is the equivalent of reading a great book whilst lacking the power of comprehension. It is a futile waste of time and energy!” (38)

I wonder if anyone has ever done the math on this. Of all the stories taking up residence in Dr. John H. Watson’s tin dispatch box at Cox & Co., in Charing Cross; of all the tales of circus belles, Hammersmith wonders, paradol chambers, amateur mendicant societies, and parsley sinking into butter on a hot day—stories that either went unwritten or unread by the general public—which story has inspired the most authors to pick up the pen and try their own hand at it? When the package from Amazon arrived containing a brand-new copy of Sherlock Holmes and the Giant Rat of Sumatra, by Paul D. Gilbert, I immediately thought of a half dozen other novel-length versions, and at least a dozen short story adaptations, of the “story for which the world is not yet prepared.” I wondered how Gilbert’s take on the story could possibly distinguish itself.

Paul Gilbert is the author of two other Sherlock Holmes outings: The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes and The Chronicles of Sherlock Holmes, which are collections of short pastiches from some of Dr. Watson’s “unpublished” accounts. Sherlock Holmes and the Giant Rat of Sumatra is his first novel-length rendering, and he is currently at work on a fourth volume, which will return to the short story format. Sherlock Holmes and the Giant Rat of Sumatra picks up in the aftermath of “The Mystery of the Mumbling Duelist,” a story that appears in The Chronicles of Sherlock Holmes. Holmes is still staggering under the repercussions of the case, although it has been some weeks since its conclusion. In his familiar, characteristic fashion, the Great Detective finds himself once again in need of mental stimulation, but he is also haunted and uneasy, before he and Watson are even called down to the London docks to investigate the abandoned tea cutter, the Matilda Briggs. Holmes has developed the mental equivalent of a “thousand-mile-stare,” and Watson is quite worried, despite Holmes’s repeated attempts to reassure his friend.

And so, Gilbert’s story immediately sets itself apart from the very first paragraph. There are no plague ships here, no genetic mutations or diabolical scientific experiments gone awry that seem so prevalent in other renditions of the tale of the “Giant Rat.” There is no hideous “Dr. Moreau”-style compound, filled with grotesque transmutations of the animal kingdom. And there are also no dangerous, desperate treks to Sumatra. Holmes and Watson stay firmly ensconced in London. The reader makes the trip to the wild, Indonesian jungle through the story that the client—Daniel Collier—shares, but it is a story told from the safety of an armchair, one neatly secure in front of a fireplace, in the familiar setting of the Baker Street sitting room.

But, perhaps most importantly, Gilbert’s Sherlock Holmes speaks with an authentic voice. He is expertly and faithfully rendered. From the moment Sherlock Holmes sets foot aboard the ghostly Matilda Briggs, there is no mistaking the Master Detective and what he has come to do. Nearly every one of his famous “methods” is present—from his knowledge of obscure powders and rare cyphers, to his intuitive understanding of the subtleties of handwriting and body language:

“This time he took out his lens and began slithering around on the boards like a viper in pursuit of its prey. Every so often he would pause for a moment or two and examine something or other with minute diligence. Occasionally he would emit a loud grunt of disappointment. Then again he might laugh to himself as he made a more positive discovery although, of course, the nature of each find would remain a mystery to the rest of us for some time” (35).

The famous Baker Street Irregulars are also present, with Wiggins at the helm, and the reader is treated to a brief glimpse of the affection Holmes feels for his collection of “Street Arabs.” The Detective provides Wiggins with instructions and wages for the group, including extra pay for some additional information. But Holmes is absolutely adamant that the extra money be spent “…on new mittens, Wiggins, not a noggin of gin” (174). In the canon, Holmes is quite open about his faith in the abilities of these ragged children, but Gilbert provides some insight into the Irregulars equivalent faith in Holmes.

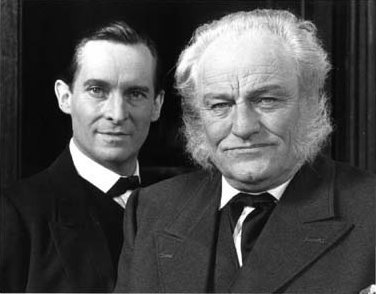

Gilbert’s Sherlock Holmes is also unique in that the author has no secrets and makes no apologies about who inspires his vision of the Great Detective. With a single glance at the cover of the “Giant Rat” (or any of Gilbert’s books), even the most feeble deductive mind sees Jeremy Brett in the starring role of these stories. In an October 15, 2010, interview with the Harrow Observer, Gilbert says:

"He was a great actor and when I write, Jeremy Brett is my Sherlock. His family have read my books and I believe they have gone down well with them… I owe a lot to Jeremy Brett. I never met him but my interpretation of Holmes owes a lot to his character."

And there is so much of Jeremy Brett’s portrayal in the book—from Holmes’s mannerisms, to his speech patterns, to even the descriptions of his wardrobe—but it is the details that are truly charming. It’s nearly impossible to envision Jeremy Brett as the Sherlock Holmes of this story, and not also see the rest of the Granada cast in their respective roles—Edward Hardwicke as Dr. Watson (the story takes place 1898, after all), Colin Jeavons as Inspector Lestrade, and Rosalie Williams as the much put-upon Mrs. Hudson.

And there are shadows of the Granada series throughout Gilbert’s writing. When Watson worries about his friend’s mental state, and surreptitiously checks a private drawer of Holmes’s desk for the infamous “neat morocco case,” there is an echo of a similar scene from the 1993 episode, “The Eligible Bachelor.” In both instances, Watson finds the needle and cocaine solution present and untouched, much “to [his] intense relief” (13). And later, when Holmes grapples with the villain at the climax of the novel, Gilbert says, “Holmes’s normally well-groomed hair was constantly falling down over his eyes and as he pushed it back, time and again, I noticed that there was evidence of numerous facial cuts and bruises that were beginning to swell around his eyes” (197). It’s quite easy to remember Brett and Patrick Allen engaged in a similar brawl, as Sherlock Holmes and Colonel Sebastian Moran, in the 1986 episode of “The Empty House.” The allusions to the Granada series are more subtle than overt, and are worked expertly into the plot—finely crafted, adding depth and dimension.

The challenge to writing any version of the “Giant Rat of Sumatra” tale is that it has a pretty heavy reputation that precedes it. To an author, it can be challenging, or even quite daunting, to attempt to write a “story for which the world is not yet prepared.” It’s a tall order, and one that not every writer is able to fill with success. Paul Gilbert’s rendering of Sherlock Holmes and the Giant Rat of Sumatra has no such problem. The plot is original, and inventive, and more than capable of revealing why this was once a story that would have shaken a man to his core. Gilbert’s Sherlock Holmes is authentic and familiar, like that comfortable chair in front of 221B Baker Street’s fireplace. That’s where some of the best stories are told, after all.

oOo

Congratulations to Chelsea Kiser! She is the winner of the Sherlock Holmes trivia contest and the copies of Sherlock Holmes Handbook, by Christopher Redmond, and Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters, by Jon Lellenberg, Daniel Stashower, and Charles Foley. For those interested, the answers to the trivia questions are as follows:

1. In later years, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle used a Parker Duofold fountain pen—specifically, the “Big Red” model, which was introduced in 1921. References to this bit of trivia can be found in Graham Moore’s The Sherlockian, and in the 2010 series, Sherlock, in the episode: “The Great Game.”

2. In The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, Dr. Watson states that “The Lion’s Mane,” “The Mazarin Stone,” “The Creeping Man,” and “The Three Gables,” are “forgeries by other hands than mine.” Watson also claims to have himself made up “The Final Problem,” and “The Empty House,” to disguise the timeframe in which Sherlock Holmes was seeking treatment for his cocaine addiction.

3. The answer I was steering readers towards was “Kilravock House,” as stated in Alistair Duncan’s Close to Holmes. I also accepted "Beaulieu Lodge," or “Hazelwood,” from Leslie Klinger’s annotations.

There will be a new contest, complete with prizes, on June 27, so please check back for a new chance to win! Thank you to everyone who participated. I hope you enjoyed the thrill of the hunt!